ARCHIVE

Vol. 9, No. 2

JULY-DECEMBER, 2019

Editorials

Research Articles

In Focus

Research Notes and Statistics

Book Review

Farmer Producer Companies in India:

Demystifying the Numbers

*Azim Premji University, annapurna.neti@apu.edu.in.

†Azim Premji University, richa.govil@apu.edu.in.

‡Research Assistant, Azim Premji University, madhushree.rao15@apu.edu.in.

Introduction

Eighty five per cent of India’s farmers are small and marginal producers, cultivating small plots that generate low returns (NSSO 2014). Bringing them together into producer enterprises is expected to give them advantages of scale that they lack as individual producers, and bring in cost efficiencies in production and marketing, better price realisation through aggregation and value addition, and risk reduction (Kanitkar 2016; NABARD 2018b; Singh 2008). Many different organisational forms of collective enterprises have been promoted in India. Cooperatives, one of the oldest forms of producer collectives, have not been able to grow into strong member-controlled and self-sustainable business entities (Shah 2016) because of excessive dependence on government funds, political interference, bureaucratisation, and corruption (GoI 2000). As an alternative, in 2000, the concept of producer companies was recommended by a committee chaired by Y. K. Alagh. These companies were designed to bring together desirable aspects of the cooperative and corporate sectors for the benefit of primary producers, especially small and marginal farmers (Alagh 2019; GoI 2000). In 2002, the Companies Act of 1956 was amended to allow for a new form of corporate entity, namely producer companies (PCs) (GoI 2011; GoI 2013).

Since then, many government schemes have relied on producer companies as vehicles to improve the economic situation of farmers and other producers such as weavers and artisans. This is evident in a number of schemes, many of which have been announced as part of Union Budgets in recent years, and administered through the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Small Farmer Agri-business Consortium (SFAC), and various government departments. The social sector too appears to be viewing farmer producer companies (FPCs) as an important part of their work on rural livelihoods, especially for improving market access and incomes of small producers. As a result, a large number of organisations are working on promoting, supporting, capacity-building, and funding of FPCs across the country.1

Several studies have analysed the performance of FPCs, and highlighted challenges such as low capital base, insufficient external finance, talent gap, operational issues, weak governance, inadequate storage and processing facilities (Singh and Singh 2014; Kanitkar 2016; Prasad 2017; Shah 2016; Govil 2018; NABARD 2018b; Mahajan 2014; Sastry 2017). However, there continues to be a gap in understanding the broad characteristics of all producer companies including their total number, distribution across states, primary activities, number of shareholders, and paid-up capital. Knowledge of these characteristics is essential for policy-making.

Some researchers have estimated the number of producer companies to be around 2,000 by relying on the annual reports of NABARD and SFAC, both of which have been mandated to administer multiple schemes for the promotion and support of producer companies (NABARD 2018a; SFAC 2018a). Others have arrived at their own estimates ranging from about 400 to 2,000 (Trebbin 2016; Shah 2016; Singh 2015). An internet search reveals various unpublished documents and news items claiming that the number ranges from 3,000 to 4,500. Recently, N. Srinivasan and G. Srinivasan (2018) estimated that 6,000 farmer producer organisations (FPOs) were operating in the country as of March 2017, most of which were FPCs.“Farmer producer organisations” (FPOs) is a broad term which includes farmer producer companies (FPCs), farmer cooperatives and societies. The term “producer companies” (PCs) refers to both farm and non-farm producer companies registered under producer company provisions of the Companies Act. In this context, “farmers” refers to those engaged in agriculture and allied activities.

As there continues to be confusion about the actual number of producer companies, as part of a larger research project on farmer producer companies, we undertook a study specifically to determine the number of producer companies registered in the country.2 This paper provides a new estimate of the number of producer companies, their geographic spread, the current status of their registration, and their authorised and paid-up capital, based on a dataset constructed using information from the Registrar of Companies under the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA).

Methodology

We collected data on all producer companies registered between January 1, 2003 and March 31, 2019 from the MCA website. First, we selected only those companies with the words “producer company” or “producers company” in their names, as the Companies Act requires the names of producer companies to have the words “producer company limited.” We checked for misspellings and typographical errors, and included the relevant names. Secondly, we corrected for duplicate entries, mismatching, and missing data fields. Thirdly, for companies with mismatching business activity codes, we verified that they were indeed registered as producer companies under Section 581 of Part IX-A of the Companies Act 1956 or Section 465 of the Companies Act 2013, by purchasing the Articles of Association and other documents.

Fourthly, we added several companies present in the lists of producer companies published by SFAC, NABARD, and other central and State government agencies, but missing in the MCA spreadsheets.

Fifthly, we updated authorised capital (AUC) and paid-up capital (PUC) by verifying the latest values available with the MCA as of April 2019. A registered company may be “struckoff” under Section 248 of Companies Act 2013 for failure to commence or maintain business activities within a stipulated time. We updated our dataset to reflect the latest status of each company (as of April 2019).

After all these corrections, we arrived at a comprehensive list of 7,374 producer companies registered between January 1, 2003 and March 31, 2019. This is the dataset used for the analysis presented in this paper.

Accuracy Estimation and Limitations of the Dataset

Our figure of a total of 7,374 producer companies registered until March 31, 2019 is double that in most previously published estimates. Our first check was to negate the possibility that a large proportion of companies in our dataset had been included erroneously (as it is possible that some companies with the words “producer company” in their name are not producer companies incorporated under the relevant Act).

We estimated the accuracy of the dataset by taking a sampling approach combined with a t-test. We verified the companies’ registrations based on lists published by NABARD, SFAC, and promoter organisations, through company websites and company incorporation documents. We found that out of the 100 companies selected randomly, 99 were registered as producer companies under relevant sections of the Companies Act, corresponding to a sample mean of 0.99. To validate this estimate, we used t-distribution statistics to determine the probability that the mean for the full population was within ±3 per cent of the sample mean. Standard t-test tables indicated that this probability was 99.8 per cent. Next, we tested another random sample to revalidate the reliability of this estimate, and found that 100 per cent of the sample companies were registered as producer companies. These tests indicated that the dataset has a high level of reliability and is adequate for the purpose of our analysis.

A second possible source of error in the dataset was that of exclusion: if a producer company did not have the words “producer company” (or their variants) in its name, it would not appear in our dataset. Third, our dataset may include companies registered as producer companies but engaged in activities which are not really intended as primary activities of producer companies.

To summarise, the analysis presented in this paper is based on a dataset of 7,374 producer companies registered between January 1, 2003 and March 31, 2019, identified on the basis of publicly available data from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, which were corrected for various types of inclusion/exclusion errors and updated as of April 2019. Statistical tests indicate that the accuracy level of this dataset is very high.

Number and Distribution of Producer Companies in India

The very first producer company registered in India was Farmers Honey Bee India Producer Company Ltd. In the first financial year after notification of the amendment, namely financial year (FY) 2004 (April 1, 2003 to March 31, 2004), a total of five producer companies were registered (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of producer companies registered, by year, India, 2003–19, in number and per cent

| Financial year (FY) | Number | Share of total PCs |

| FY 2004 | 5 | <1 |

| FY 2005 | 16 | <1 |

| FY 2006 | 24 | <1 |

| FY 2007 | 32 | <1 |

| FY 2008 | 18 | <1 |

| FY 2009 | 41 | <1 |

| FY 2010 | 28 | <1 |

| FY 2011 | 52 | 1 |

| FY 2012 | 78 | 1 |

| FY 2013 | 151 | 2 |

| FY 2014 | 497 | 7 |

| FY 2015 | 551 | 7 |

| FY 2016 | 1691 | 23 |

| FY 2017 | 1477 | 20 |

| FY 2018 | 909 | 12 |

| FY 2019 | 1804 | 24 |

| Total | 7374 | 100 |

In the first 10 years after notification of the act (FY 2004 through FY 2013), a total of only 445 companies were registered. The pace of registration accelerated during FY 2014, when 497 producer companies were registered, a number that exceeded all previous 10 years combined (Figure 1). The number of companies registered crossed 1,000 for the first time in FY 2016. In the most recent three financial years (FY 2017, FY 2018, FY 2019), 4,190 producer companies were registered, amounting to an average of almost four companies per day with one of the four being registered in Maharashtra.

Figure 1 Number of producer companies registered, by year, all-India, 2003–19, in numbers

This massive jump in registrations in recent years as observed in the MCA data coincides with various State and central government schemes. Most such schemes for the promotion and support of FPOs in general, and FPCs in particular, came into effect in FY 2013, FY 2014, and FY 2015. There was an observable drop in producer company registrations in FY 2018, which appears to be correlated with the completion of the term of NABARD’s PRODUCE programme.3

The relationship between producer company registrations and government schemes is also evident in the number of registrations that took place in the last quarter of each financial year. In the last five financial years (FY 2015 to FY 2019), a disproportionate number of producer companies (34 per cent) were registered during January to March, possibly indicating a rush to register companies to meet programmatic milestones.

State-wise Distribution of Producer Companies

Producer companies have been registered in 33 out of 36 States and Union Territories in India. Maharashtra has by far the largest number of producer companies (1,940), which is more than the next three States combined. Four States – namely, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Madhya Pradesh – account for about half the producer companies registered until March 31, 2019 (Table 2).

Table 2 Number of producer companies registered, by State or Union Territory, all-India, 2003–19, in number and per cent

| State/Union Territory | Number | Share of total PCs |

| Maharashtra | 1940 | 26 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 750 | 10 |

| Tamil Nadu | 528 | 7 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 458 | 6 |

| Telangana | 420 | 6 |

| Rajasthan | 373 | 5 |

| Karnataka | 367 | 5 |

| Odisha | 363 | 5 |

| Bihar | 303 | 4 |

| Haryana | 300 | 4 |

| West Bengal | 274 | 4 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 238 | 3 |

| Kerala | 215 | 3 |

| Gujarat | 183 | 2 |

| Jharkhand | 133 | 2 |

| Chhattisgarh | 114 | 2 |

| Assam | 112 | 2 |

| Delhi | 57 | 1 |

| Punjab | 56 | 1 |

| Uttarakhand | 37 | 1 |

| Manipur | 30 | <1 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 22 | <1 |

| All other | 101 | 1 |

| Total | 7374 | 100 |

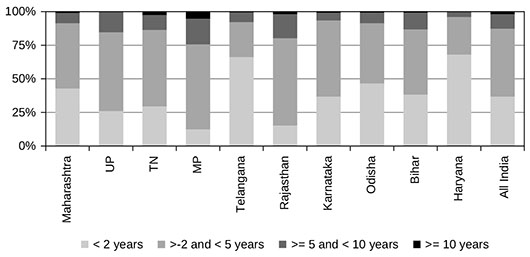

Madhya Pradesh, which has the fourth largest number of registered producer companies, started promoting producer companies early under the District Poverty Initiative Programme. Madhya Pradesh also has the highest percentage of companies which are five years or older (Figure 2). Uttar Pradesh, on the other hand, hardly has any producer companies older than 10 years. Uttar Pradesh started later than other “top” States in producer company formation, but rapidly caught up, surpassing Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu in FY 2014. Telangana and Haryana have a large percentage (66 per cent and 68 per cent, respectively) of very young companies.

Figure 2 Distribution of registered producer companies for top 10 States, by age, 2019, in per cent

We analysed the district-wise distribution of producer companies by mapping their registered addresses on to names of districts as per Census 2011. Not surprisingly, we found that across India, nine out of the top 10 districts with the most number of producer companies were in Maharashtra. Within Maharashtra, Pune and Ahmednagar districts had the largest number of producer companies (more than 150 each), while at the other end, Ratnagiri and Gadchiroli had less than 15 each. In Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow had the most number of producer companies (about 70), followed by Kanpur and Varanasi, while many other districts had less than five producer companies each. In Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore and Erode had the largest number of producer companies (about 40 each), and the remaining districts appeared to have a more even spread in terms of the number of producer companies. These data suggest a significant disparity in the number of producer companies across districts, pointing towards the need for re-assessing the geographical focus of efforts to promote producer companies.

Active and Struck-off Companies

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs “strikes off” companies for three reasons specified under the Companies Act 2013, Section 248: (i) failure to commence business operations within one year of incorporation, (ii) failure of original subscribers (shareholders) to fully pay committed subscription (share capital) within 180 days of registration, and (iii) failure to carry out any business or operation for a period of two immediately preceding financial years without applying within that period for the status of a dormant company under Section 455. In addition, the MCA can strike off producer companies for failure to maintain any of the mutual assistance principles specified under Section 581ZP.

A total of 445 producer companies have been struck off or are in the process of being struck off by the MCA, corresponding to 6 per cent of all producer companies registered. Only three companies have been designated as dormant so far. In fact, the very first producer company registered under the Act, Farmers Honey Bee India Producer Company Ltd., has been struck off by the MCA.

While the “struck off” percentage may appear small, it is important to note that companies can be struck off only after two years of failing to maintain operations, and after they have been given time to respond to Ministry notifications. Therefore, in the early years of a producer company, there is little scope for the MCA to strikeoff the company. Table 3 shows that only a small proportion of young companies have been struck off. However, among producer companies which are 10 years and older, more than 46 per cent have been struck off.

Table 3 Producer companies struck off by the MCA, by age, in number and per cent

| Age of company | Number | As % of all PCs in the same age category | Total PCs |

| <2 years | 3 | 0 | 2713 |

| >=2 and <5 years | 72 | 2 | 3719 |

| >=5 years and <10 years | 310 | 38 | 806 |

| >=10 years | 63 | 46 | 136 |

| Total | 448 | 6 | 7374 |

Note: For simplicity, struck-off columns include companies struck off, under process of being struck off, and dormant companies: only three companies are dormant, 22 companies are in the process of being struck off, and the rest have been struck off.

It is important to note here that the percentage of struck-off companies should not be read as a “death rate,” as striking off by MCA will always underestimate the actual death rate due to the time lag in review, and also because some companies may continue to fulfil compliance requirements despite not engaging in any business activities. Therefore, at any given point in time, we can expect the actual “death rate” to be higher than the struck-off percentage.

Number of Shareholders

The number of shareholders in a producer company can range from 10, which is the minimum required to register a producer company, to over 100,000, for a large milk producer company like Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producers Company (Ramana, n.d.). Typically, companies have a few hundred shareholders; it is only large milk producer companies which have more than 10,000 shareholders.

As shown in Table 4, NABARD reports that 86 per cent of FPOs supported by it have 500 or fewer shareholders (NABARD 2018a). Only 1 per cent of FPOs have more than 1,000 shareholders. NABARD reports that as of March 31, 2019, it had promoted 2,075 FPOs with a total of 765,000 “shareholder-members” (NABARD 2019), averaging 369 shareholders per FPO.4

Table 4 Distribution of NABARD-supported farmer producer organisations (FPOs) by membership, in per cent

| No. of shareholders or members | % of FPOs |

| Upto 50 | 16 |

| 51–100 | 14 |

| 101–500 | 56 |

| 501–1000 | 13 |

| Above 1000 | 1 |

| All membership categories | 100 |

Source: NABARD Annual Report 2017–18, Table 2.2.

As of July 31, 2019, SFAC had supported 819 registered FPOs, covering 820,000 producers with an average of 997 shareholders per FPO (SFAC 2019).

Taking a weighted average of NABARD- and SFAC-supported companies (and assuming that the FPO average can be applied to FPCs), we arrive at an average of 582 shareholders per producer company. Thus, we estimate that over 4.3 million small producers in the country have become members of and contributed share capital towards 7,374 producer companies.5

Paid-Up Capital

The MCA database includes information on authorised capital and paid-up capital of registered companies. To capture the latest available data, we updated information on authorised and paid-up capital for all 7,374 producer companies.

We estimated that registered producer companies have a total authorised capital of about Rs 15.7 billion and total paid-up capital of about Rs 8.6 billion, with an average of Rs 1.17 million per company (Table 5). However, it is important to note that a few companies have very high paid-up capital. For example, of the Rs 8.6 billion paid-up capital, Rs 2.1 billion is for just one company, namely, Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producers Company Ltd. The paid-up capital of the top 100 companies including Sri Vijaya Visakha adds up to Rs 5.9 billion, amounting to more than two-thirds of the total paid-up capital. At the other end, there are 189 companies each with paid-up capital of Rs 1000 or less. Given this distribution, we examine the median (rather than mean) paid-up capital, which is Rs 106,000 for all registered companies and Rs 110,000 for companies with “active” registration status.

Table 5 Aggregate characteristics of producer companies registered by status as of March 31, 2019, in number

| PCs registered | PCs with “active” status | |

| Total number of producer companies | 7,374 | 6,926 |

| Average number of shareholders per company | 582 | 582 |

| Total number of shareholders | 4.3 million | 4 million |

| Total paid-up capital | Rs 8.6 billion | Rs 8.4 billion |

| Average paid-up capital per producer company | Rs 1.17 million | Rs 1.22 million |

| Median paid-up capital per producer company | Rs 106,000 | Rs 110,000 |

| Average paid-up capital per shareholder | Rs 2,003 | Rs 2,092 |

In the previous section, we estimated that there are about 4.3 million shareholders across all producer companies. This estimate allows us to calculate the average share capital per producer-shareholder to be Rs 2,003. For companies with “active” status, this figure is Rs 2,092 per shareholder. Here, too, the median would be the more appropriate measure, as a few shareholders with very high contribution would skew the mean. However, it is not possible to calculate the median as shareholder data are not available for each company.

Since it does not make sense to analyse paid-up capital for companies which have been struckoff, the rest of the analysis presented here is only for companies with “active” status.

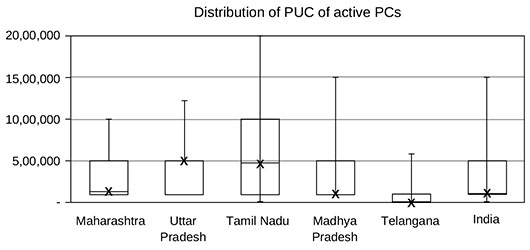

Figure 3 shows the distribution of paid-up capital across all active companies in the top five States and nationally. The distribution of paid-up capital is highly skewed across India. In the top five States, median paid-up capital ranged from Rs 10,000 to Rs 0.5 million. Tamil Nadu had many companies with high paid-up capital, while Telangana had mostly smaller ones. Most of the producer companies in Telangana were very young (less than two years) and were formed after the MCA eliminated the minimum paid-up capital requirement. Such differences in median paid-up capital reflect the different histories and methods of producer company promotion across States.6

Figure 3 Distribution of paid-up capital of producer companies in top five States and all-India for active producer companies.

Notes: (i) The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentile, while the “whiskers” indicate extent of the 5th and 95th percentile. (ii) The line with an ‘x’ indicates median. (iii) The 95th percentile for Tamil Nadu is at 2.05 million.

To analyse the distribution of paid-up capital across all producer companies in further detail, we classified producer companies into four categories: category A with paid-up capital of Rs 5 million or more, category B with paid-up capital of Rs 2.5 million (inclusive) to Rs 5 million (exclusive), category C with paid-up capital of Rs 1 million (inclusive) to Rs 2.5 million (exclusive), and category D with PUC of less than Rs 1 million.

Table 6 shows that about 86 per cent of “active” producer companies were very small with less than Rs 1 million of paid-up capital, falling in category “D.” Only about 2.6 per cent of active companies had paid-up capital greater than Rs 2.5 million, falling in categories “A” or “B.”

Table 6 Number of producer companies by paid-up capital for active status companies, in number and per cent

| PUC category | Definition | No. of “active” PCs | % of total |

| Category A | PUC >=5 million | 90 | 1.3 |

| Category B | PUC >=2.5 and <5 million | 87 | 1.3 |

| Category C | PUC >=1 and <2.5 million | 767 | 11.1 |

| Category D | PUC <1 million | 5,982 | 86.4 |

| of which: | |||

| PUC >=0.5 and <0.1million | 1,465 | 21.2 | |

| PUC >0.1 and <0.5 million | 1,146 | 16.5 | |

| PUC = 0.1 million | 2,680 | 38.7 | |

| PUC <0.1 million | 691 | 10 | |

| All categories | 6,926 | 100 |

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding off.

Large producer companies (category A) appear to be concentrated in a few States (Table 7). Kerala has the highest number of producer companies in category “A,” with PUC of more than Rs 5 million. Many of these companies have been promoted under government schemes, such as those under the Coconut Development Board. We visited one such coconut producer company and found that the average share capital contributed per member was about Rs 5,400, with the minimum being Rs 2,500 and maximum being Rs 0.1 million. Many of the shareholders in the coconut PC were engaged in full-time jobs with coconut farming as a secondary source of income. This additional source of income may partially explain their capacity to contribute higher share capital as compared to the average small producer.

Table 7 Top 10 States with highest number of category “A” producer companies, by paid-up capital, in number

| State | Paid-up capital category (in millions) | Total PCs | |||

| A >=5 | B >=2.5 and <5 | C >=1 and <2.5 | D <1 | ||

| Kerala | 28 | 16 | 28 | 133 | 205 |

| Maharashtra | 11 | 17 | 126 | 1,723 | 1,877 |

| Tamil Nadu | 5 | 14 | 135 | 333 | 487 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 5 | 5 | 35 | 368 | 413 |

| Haryana | 5 | 4 | 38 | 251 | 298 |

| Telangana | 5 | 2 | 10 | 383 | 400 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 5 | 2 | 10 | 207 | 224 |

| Karnataka | 4 | 5 | 125 | 225 | 359 |

| Rajasthan | 4 | 1 | 16 | 307 | 328 |

| Assam | 3 | 4 | 9 | 91 | 107 |

Note: Includes only companies with “active” status.

Despite Maharashtra having the highest number of producer companies, the number of producer companies with share capital greater than Rs 5 million is only 11, which is less than half that of Kerala. Other States have even fewer numbers of large companies. Interestingly, Uttar Pradesh, the State with the second largest number of producer companies, does not feature in this list of top 10 States with category A producer companies.

It is important to note that larger paid-up capital does not necessarily imply higher turnover and profits. It does, however, indicate availability of funds for higher trading volumes, investment in fixed assets, value addition, and other purposes. In principle, it also indicates the possibility of leveraging capital to raise working capital and term loans for business operations. Thus, paid-up capital indicates the possibility of a business growing, generating returns for shareholders, and becoming viable in the longrun.

One of the main reasons for promoting producer companies is that they offer an avenue for pooling small amounts of capital from large numbers of people into greater sums for creating scalable and viable businesses. However, as shown above, the majority of companies are undercapitalised. One promoting institution we interviewed, which has promoted more than 100 companies, estimates that an FPC working with foodgrain farmers requires funds of at least Rs 30,000 per member (Rs 10,000 for providing inputs and Rs 20,000 for trading in foodgrains). This implies that a small FPC with 200 members would require Rs 6 million for smooth operation.7 But the current median paid-up capital is only about Rs 0.1 million, which is much lower than that needed for commencing and maintaining business activities at a reasonable scale. It is unlikely that such a large deficit can be compensated by loans.

Next, we examine whether paid-up capital increases with the age of producer companies (Table 8). Among older companies, a larger proportion had paid-up capital greater than Rs 5 million, as compared to younger companies. Nevertheless, we found that 59 per cent of older companies (10+ years) continue to have paid-up capital of less than Rs 1 million.

Table 8 Distribution of producer companies, by PUC and age, in numbers and per cent

| PUC category | Age of producer company | All ages | |||

| Less than 2 years | >=2 and <5 years | >=5 and <10 years | 10 years or more | ||

| A >=5 million | 14 1% | 31 1% | 28 6% | 17 23% | 90 1% |

| B >=2.5 and <5 million | 4 0% | 53 1% | 26 6% | 4 5% | 87 1% |

| C >=1 and <2.5 million | 208 8% | 462 13% | 88 18% | 9 12% | 767 11% |

| D <1 million | 2484 92% | 3101 85% | 354 71% | 43 59% | 5982 86% |

| Total | 2710 100% | 3647 100% | 496 100% | 73 100% | 6926 100% |

Note: Includes only companies with “active” registration status. Percentages may not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding off.

Paid-up capital also appears to be linked to the likelihood of being struckoff. Our analysis shows that among producer companies which are five years or older, the likelihood of being struck off decreases with higher paid-up capital. About 45 per cent of category D companies had been struck off, but only 4 per cent of category A companies had been struck off. This could be due to multiple reasons. It could be because companies with greater capital are likely to have more robust business operations while undercapitalised companies may be struggling to keep their business afloat. Or it could be that companies with a larger capital base may have more established operations, and can afford to hire accountants to prepare and submit audited financials to the MCA and meet compliance requirements. This relationship might also be due to another factor: it is possible that some resource institutions promote robust companies which have both characteristics (higher paid-up capital and better compliance with MCA requirements).

Top 20 Producer Companies by Paid-Up Capital

We examined the largest 20 producer companies in terms of paid-up capital to get a better understanding of the characteristics of large companies. As shown in Table 9, eight of these top 20 companies were less than five years old, which shows that many of them were able to raise significant capital fairly quickly. Seven of the companies are located in Kerala and supported by the Coconut Development Board. In terms of sectoral activities, out of the top 20 companies, 10 are dairies, eight are plantations (mostly coconut), one is cultivation-related (fruits and vegetables) and one works in poultry.8 Five of the 10 dairies are cooperatives which were subsequently converted to producer companies. The Madhya Pradesh Poultry Company was also converted from a cooperative to a producer company (MPWPCL n.d.). It seems that cultivation-focused companies find it difficult to raise large amounts of capital as only one cultivation company appears in the top 20 list. It is also pertinent to note that Sahyadri FPCL, the only cultivation company in the top 20 list, is a self-funded company with more than 8,000 shareholders, of whom several are large farmers who have contributed millions in share capital (Sahyadri FPCL n.d.; Sahyadri FPCL 2018).

Table 9. Top 20 producer companies with largest paid-up capital, by sector, year of registration, State

| Name of company | Paid-up capital (in million Rs) | Sector | Women only | Registration | State |

| Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producers Co. | 2130 | Dairy | FY06 | Andhra Pradesh | |

| Sahyadri Farmers Producer Co. | 550 | Fruits and vegetables | FY11 | Maharashtra | |

| Sangam Milk Producer Co. | 500 | Dairy | FY14 | Andhra Pradesh | |

| Paayas Milk Producer Co. | 370 | Dairy | FY13 | Rajasthan | |

| Maahi Milk Producer Co. | 350 | Dairy | FY13 | Gujarat | |

| Saahaj Milk Producer Co. | 230 | Dairy | FY15 | Uttar Pradesh | |

| Karimnagar Milk Producer Co. | 160 | Dairy | FY13 | Telangana | |

| Shreeja Mahila Milk Producer Co. | 140 | Dairy | Yes | FY15 | Andhra Pradesh |

| Baani Milk Producer Co. | 100 | Dairy | FY15 | Punjab | |

| Shree Chhatrapati Shahu Milk and Agro Producer Co. | 100 | Dairy | FY09 | Maharashtra | |

| Madhya Pradesh Women Poultry Producers Co. | 60 | Poultry | Yes | FY07 | Madhya Pradesh |

| Karimnagar Milk Farmers Development Producer Co. | 50 | Dairy | FY17 | Telangana | |

| Vadakara Coconut Farmers Producer Co. | 40 | Coconut | FY16 | Kerala | |

| Begoti Tea Producer Co. | 40 | Tea | FY14 | Assam | |

| Palakkad Coconut Producer Co. | 40 | Coconut | FY14 | Kerala | |

| Perambra Coconut Producer Co. | 30 | Coconut | FY15 | Kerala | |

| Thirukochi Coconut Producer Co. | 30 | Coconut | FY14 | Kerala | |

| Tirur Coconut Producer Co. | 30 | Coconut | FY15 | Kerala | |

| Onattukara Coconut Producer Co. | 30 | Coconut | FY15 | Kerala | |

| Kaipuzha Coconut Producer Co. | 30 | Coconut | FY14 | Kerala |

Most of the top 20 companies have received some form of government support, either as cooperatives or as producer companies (or both). While one cannot attribute their achievements to government support alone, most of the companies that we interviewed valued the government support they received during their formative years.

Companies with Low Paid-Up Capital

We next examine companies in category D more closely.

Table 10 shows that 42 per cent of category D companies were less than two years old. The vast majority (58 per cent) were two years or older, but apparently had not been able to increase their capital to a significant level.

Table 10 Age distribution of companies with less than Rs 1 million of paid-up capital, in number and per cent

| Age category (in years) | Number | % of total |

| <2 | 2,484 | 42 |

| >=2 and <5 | 3,101 | 52 |

| >=5 and <10 | 354 | 6 |

| >=10 | 43 | 1 |

| All ages | 5,982 | 100 |

Note: Only shows companies with active status. Percentages may not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding off.

We further classified category D companies into 4 categories: companies with PUC below Rs 0.1 million, exactly Rs 0.1 million, between Rs 0.1 and Rs 0.5 million, and between Rs 0.5 to 1 million (Table 6). About 21 per cent of all companies had paid-up capital between Rs 0.5 and Rs 1 million. Thirty-nine percent of the 6,926 active producer companies had paid-up capital of exactly Rs 0.1 million. This is understandable because until recently companies needed a minimum paid-up capital of Rs 0.1 million to be able to be incorporated under the Companies Act. However, it is worth noting that these companies had not increased their paid-up capital since then. The requirement of a minimum of Rs 0.1 million minimum paid-up capital for the incorporation of companies was eliminated in 2015 for all private limited companies, not just producer companies (GoI 2015).

We may conclude that out of 6,926 active producer companies, 3,498 (51 per cent) continue to have very low levels of paid-up capital even two or more years after incorporation. This is worrying because such low PUC limits a company’s ability to carry out business activities.

Discussion

Data for Policy Analysis and Regulation

While information on whether a company is registered as a producer company is captured by the MCA at the time of registration, this data-field is not made available by the Ministry in the spreadsheets uploaded on its website. Currently, all producer companies are treated as equivalent to private limited companies under the Companies Act and, as such, the company identification number (CIN) of producer companies has the same letters (PTC) as any other private limited company.9 Therefore, going by the CIN number (and the name), it is not possible to identify whether a company is a producer company or not. One way to address this issue could be to create a new marker in the CIN schema to designate producer companies.

Secondly, we identified 37 producer companies with incorrect company-type codes (that is, codes other than “PTC”) in their CIN. Avoiding these kinds of issues requires better training of the Registrar of Companies staff and ongoing vigilance to correct errors made at the time of incorporation.

Thirdly, we came across companies registered as producer companies under the relevant sections of the Companies Act, but engaged in providing deposit and credit services as their primary activity and not as an ancillary activity for primary producers. To prevent such cases, the MCA should clarify the types of activities that can be undertaken by producer companies as primary activities.

Fourthly, the MCA should make available more details about producer companies (e.g., total number of shareholders in each company) to the public. Reliable data on producer companies is important for regulatory purposes, to be able to introduce differentiated regulatory requirements for different categories of companies. For example, NABARD (2018b) recommends “suitable relief to FPOs from various statutory compliances . . . at least during initial 10 years so as to help them adjust with the regulatory business environments and stabilise business operations.” Any such effort would require tracking and regulating producer companies separately from other private limited companies.

To summarise, basic data on producer companies is necessary for analysing the impact of current policies and for effective regulation. This is particularly important because producer companies are being formed with social objectives using government funds. The current approach towards collection and access of data relating to producer companies makes this difficult, which could be one of the reasons that most studies of producer companies that have been published to date have focused on ground-level operational and financial challenges to the collection of data through primary surveys.

Undercapitalised Producer Companies

Central and State governments appear to view producer companies as key to improving the incomes of small producers, and have disbursed substantial sums to promote and support producer companies through NABARD, SFAC, and various government departments such as Department of Horticulture. Many private philanthropies and CSR organisations also fund producer companies.

The outcome of this effort over the last 17 years has been the incorporation of thousands of producer companies, covering an estimated 4.3 million small and marginal producers, as shareholders. The typical producer company in India today is engaged in farm-related activities and has paid-up capital of about Rs 0.1 million. This amount is inadequate to carry out substantial business activities or to have a significant impact on the incomes of their members. Previous studies have also pointed out that equity mobilisation of producer companies must be higher in order to create member interest and patronage (Kanitkar 2016; Singh 2016).

While paid-up capital is not the only determinant of a company’s success, it does indicate the potential of a company in terms of its trading volumes, turnover, ability to raise working capital and term loans, etc. Our interviews with a large number of producers, board members, CEOs, promoting institutions, funders, and other stakeholders also validate these findings – most companies with low paid-up capital are struggling to initiate and maintain business operations.

In principle, there are five ways to increase the funds available to a company: (i) increase members’ contribution, (ii) equity grants, (iii) leverage equity to avail of term loans, (iv) raise working capital loans, and (v) generate surplus by running a profitable business.

Our discussions with multiple promoters and producers revealed that producers are hesitant to contribute share capital to young companies; this is consistent with the observations made in previous studies (Kanitkar 2016).

The second approach of equity grants has been tried by SFAC and others to help producer companies with marginal producers increase their equity. NABKISAN estimates that new producer companies require Rs 1.5–2 million for starting operations, with at least Rs 0.3–0.5 million coming from equity (NABKISAN n.d.). Currently, the typical median producer company has a paid-up capital of only Rs 110,000, leaving a gap of about Rs 300,000. If this equity gap has to be raised from grants, a one-to-one equity grant is inadequate; instead, it would require a 3:1 match. An alternative could be to enable private capital to invest in FPCs. NABARD has proposed amending the Companies Act to make provision for equity participation by private investors to strengthen FPC balance sheets and improve their commercial viability, along the lines of the finance ecosystem for commercial start-ups (NABARD 2018b). In such a scenario, the social objectives of the FPCs can be maintained by enabling private investment through a different class of shares (for example, shares with no voting rights).

The third and fourth approaches to raise funds are through short- and long-term loans. Most producer companies do not have enough equity or fixed assets to raise loans. Banks are extremely hesitant to offer loans to producer companies against inventory as collateral. And despite initiatives such as credit guarantee schemes and inclusion of loans of up to Rs 20 million for FPOs under priority sector lending (RBI 2015), formal financial support for FPOs remains weak. “Access to affordable credit is limited for want of collateral and credit history” (NABARD 2018a).

As formal financial sources are not easily accessible, some producer companies resort to borrowing from informal sources.10 We also came across multiple cases where SHG federations gave working capital loans to affiliated “sister” producer companies with largely overlapping membership. This is a risky approach as the source of funds for SHG federations are the savings of members who are already financially vulnerable and who may not be in a position to evaluate the risk/return of lending to producer companies; any default by the producer company would result in a loss of their savings (Govil, Neti, and Rao 2020). Furthermore, in principle, SHG federations are expected to lend only to their member groups and not to external entities such as FPCs, despite a significant overlap in membership.

The fifth approach of generating surplus seems to be a distant goal for most producer companies. Many companies struggle to run business operations (for lack of working capital) and generate profits. In fact, in many cases, instead of increasing equity through retained earnings, their total equity is eroding due to repeated losses. Thus, for producer companies with low equity, none of the above approaches for raising funds seem feasible.

These are possible ways to address the problem of under-capitalised producer companies:11

- For undercapitalised companies, stakeholders should assess performance and future potential. Companies with strong business potential can be supported through additional grant and loan schemes (subject to the achievement of certain milestones), while continuously loss-making enterprises may have to be wound up.

- Options and mechanisms for enabling private investment in producer companies without diluting their social purpose should be evaluated.

- It may also be necessary to establish more stringent conditions with regard to membership and capitalisation before registering new companies.

Concluding Remarks

Well-run and stable producer companies have the potential to improve farmers’ incomes and reduce their exposure to economic risk. Therefore, it is not surprising that government and non-government organisations are increasingly viewing them as essential components of their long-term vision for economic development.12

However, the majority of the 6,926 companies in existence today are undercapitalised, as shown in this note.

Roughly 4.3 million producers (most of them small and marginal) have already contributed Rs 8.6 billion towards share capital in 7,374 producer companies. Policy-makers have a fiduciary and ethical responsibility to ensure that these funds, contributed by small producers from their meagre savings, are used effectively to generate returns, rather than lying unused due to inadequate working capital or being depleted due to loss-making operations. Ensuring this requires better understanding of the impact of currently registered producer companies, proactive monitoring and regulation of these companies, and modification (as needed) of existing policies and regulations.13 This is all the more important and urgent in the light of the recent announcement to promote an additional 10,000 FPOs, raising the total coverage to about 10 per cent of all agricultural households in India, most of whom are small and marginal farmers.

Acknowledgements: This study has been supported by the Azim Premji University and Self-Reliant Initiatives through Joint Action (SRIJAN). We are grateful to the many producer company members, boards of directors, promoters, and other stakeholders who contributed to this study by generously sharing their time, expertise, and insights. We thank Khyati Sharma, Niyati Gadepalli, Roshni Lobo, and Sharat Kumar for their assistance with data verification, and Sheetal Patil for help with data representation. We also thank the anonymous referee for valuable suggestions.

Notes

2 This quantitative study is part of a larger study on producer companies, which includes more than 100 separate interviews with farmers, board members, promoters, funders, and other stakeholders in producer companies, and personal visits to 18 producer companies.

4 Here we are assuming that the average number of shareholders in FPCs is the same as that in all FPOs.

5 In some producer companies, shares are held directly by individual shareholders, while in others they are held collectively by cooperatives, farmer groups, self help groups (SHGs), and, in some cases, even other FPCs. For the purpose of the analysis above, we have focused on the effective size of producer membership as the capital is contributed ultimately by the members of these groups.

6 Our interviews revealed a wide range of shareholding patterns among producer companies. For example, in one of the companies we visited, the share capital per farmer was around Rs 200, while in a couple of companies, it was around Rs 0.1 million. In one large producer company, the largest shareholder had contributed about Rs 90 million.

7 For early stage producer companies, NABKISAN estimates that Rs 1.5–2 million is required to commence operations, of which Rs 0.3–0.5 million must come from equity which can be leveraged 4:1 for loans (NABKISAN n.d.).

8 The two Karimnagar producer companies appear to be sister companies, with three shared directors. However, they have distinct company identification numbers (CINs) and financials. The second company appears to have been formed later, focusing on processing milk into value-added products.

9 The MCA assigns a company identification number (CIN) to every registered company. For example, the largest producer company, Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producers Company Ltd., has the CIN “U15209AP2006PTC048708,” where the letters “PTC” indicate the type of company (in this case, a private limited company). Other codes used by the MCA include “PLC” to indicate public limited companies and “GoI” to indicate government-owned companies. The MCA could assign a new code (say, PRC) to identify producer companies as a separate category from private companies.

10 In our larger study, we encountered one case where the village pradhan, who was also a member of the producer company, extended a loan to the company from his personal funds. In another case, a local large trader contributed a significant amount of share capital as a gesture of goodwill and support, even though he conducted his personal trading activities outside the company.

11 This is not to imply that producer companies will become successful once the problem of under-capitalisation is addressed.

12 The central government recently announced a plan to promote 10,000 more producer companies over the next five years.

13 For full set of recommendations from the larger study, please see Govil, Neti, and Rao (2020).

References

| Alagh, Y. K. (2019), “Companies of Farmers,” in Amar K. J. R. Nayak (ed.), Transition Strategies for Sustainable Community Systems: Design and Systems Perspectives, Springer, Cham. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2000), Report of the High Powered Committee for Formation and Conversion of Cooperative Business into Companies, Department of Company Affairs, Ministry of Law, Justice, and Company Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2011), Companies Act, 1956, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2013), Companies Act, 2013, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Government of India (GoI) (2015), The Companies (Amendment) Act, 2015, No. 21 of 2015, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, 2015. | |

| Govil, Richa (2018) “Agricultural Livelihoods: Need for Reimagination,” in Narasimhan Srinivasan (ed.), State of India’s Livelihoods Report 2018, Access Development Services, New Delhi. | |

| Govil, Richa, Neti, Annapurna, and Rao, Madhushree (2020), Farmers Producer Companies: Past, Present and Future, Report, Azim Premji University, Bangalore. | |

| Kanitkar, Ajit (2016), The Logic of Farmer Enterprises, Occasional Publication 17, Institute of Rural Management Anand (IRMA), Anand. | |

| Madhya Pradesh Women Poultry Producers Company Private Limited (MPWPCL) (n.d.), “About Us,” MPWPCL, Bhopal, available at https://mpwpcl.org/about, viewed on July 10, 2019. | |

| Mahajan, Vijay (2014), “Farmer Producer Companies: Need for Capital and Capability to Capture the Value Added,” in Shankar Dutta (ed.), State of India's Livelihoods Report 2014, Access Livelivehood Services, Oxford University Press, New Delhi. | |

| National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) (2018a), Annual Report 2017–18, National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, Mumbai. | |

| National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) (2018b), “Farmer Producers’ Organisations (FPOs): Status, Issues and Suggested Policy Reforms,” National Level Paper, Potential Linked Plans (PLP) 2019–20, National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, Mumbai. | |

| National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) (2019), Annual Report 2018–19, Mumbai. | |

| NABKISAN Finance Limited (n.d.), Financing of FPOs, NABKISAN Finance Limited, Mumbai, available at https://www.nabkisan.org/products.php, viewed on July 1, 2019. | |

| National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) (n.d.), “National Dairy Plan I: Project Implementation Arrangements,” NDDB, Anand, available at https://www.nddb.coop/ndpi/about/pia, viewed on July 1, 2019. | |

| National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) (2014), “Key Indicators of Situation of Agricultural Households in India,” NSS 70th Round, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi. | |

| Prasad, C. Shambu (2017), Framing Futures: National Conference on Farmer Producer Organisations, Institute of Rural Management Anand (IRMA), Anand. | |

| Ramana, S. V. (n.d.), “Conversion from Co-operative to Producer Company: Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producer Company Limited,” Dairy Knowledge Portal, available at https://www.dairyknowledge.in/sites/default/files/shri_ramanna_exeperience_conversion_of_co-operative_in_pc.pdf, viewed on July 1, 2019. | |

| Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (2015), “Master Circular – Priority Sector Lending: Targets and Classification, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, July 1. | |

| Sahyadri Farmer Producer Company Ltd. (2018), Annual Report 2017–18, Sahyadri FPCL, Nashik. | |

| Sahyadri Farmer Producer Company Ltd. (n.d.), Sahyadri Farms, Nashik, available at http://www.sahyadrifarms.com/index.php, viewed on July 10, 2019. | |

| Sastry, Trilochan (2017), “Financial Inclusion in Capital Markets: Challenges and Opportunities for Producer Companies,” Working Paper No. 555, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore. | |

| Shah, Tushaar (2016), “Farmer Producer Companies: Fermenting New Wine for New Bottles,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 51, no. 8, February 20. | |

| Singh, Sriram (2015), “Promotion of Milk Producer Companies: Experience of NDS,” National Dairy Development Board, presentation available at https://www.dairyknowledge.in/sites/default/files/shri_sriram_singh_promotion_of_pc_nds.pdf, viewed on June 17, 2019. | |

| Singh, Sukhpal (2008), “Producer Companies as New Generation Cooperatives,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, no. 20, May 17. | |

| Singh, Sukhpal (2016), “Smallholder Organisation through Farmer (Producer) Companies for Modern Markets: Experiences of Sri Lanka and India,” in Bijman Jos, Muradian Roldan, and Schuurman Jur (eds.), Cooperatives, Economic Democratisation and Rural Development, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham. | |

| Singh, Sukhpal, and Singh, Tarunvir (2014), Producer Companies in India: Organisation and Performance, Allied Publishers, New Delhi. | |

| Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium (SFAC) (2018a), Annual Report 2017–18, Society Promoted by Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, pp. 21–22. | |

| Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium (SFAC) (2018b), “Empanelled RIs,” SFAC, Society Promoted by Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, available at http://sfacindia.com/EmpanelledRIs.aspx, viewed on July 4, 2019. | |

| Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium (SFAC) (n.d.), “List of FPOs Registered under 2 Year Programme,” SFAC, Society Promoted by Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, available at http://sfacindia.com/PDFs/List-of-FPO%20identified-by-SFAC/Statewise%20list%20of%20FPOs%20registered%20under%202%20year%20programme.pdf, viewed on July 10, 2019. | |

| Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium (SFAC) (2019), “State-Wise Progress of FPO Promotion as on 31.07.2019,” Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, available at http://sfacindia.com/UploadFile/Statistics/State%20wise%20summary%20of%20registered%20and%20the%20process%20of%20registration%20FPOs%20promoted%20by%20SFAC.pdf?data=2356.1456, viewed on December 4, 2019. | |

| Srinivasan, Narasimhan, and Srinivasan, Girija (2018), State of India’s Livelihoods 2017, ACCESS Development Services, Sage India, New Delhi. | |

| Trebbin, Anika (2016), “Producer Companies and Modern Retail: Current State and Future Potentials of Interaction,” in N. Chandrasekhara Rao, R. Radhakrishna, Ram Kumar Mishra, and Venkata Reddy Kata (eds.), Organised Retailing and Agri-Business: India Studies in Business and Economics, Springer India. |